Meet the Greebles. (In pursuit of alternative deep learning tutorial set)

Tired of MNIST?

Most aspiring data scientists have at least heard of neural networks and “deep learning” by now, and you’ve probably noticed that deep learning has been getting really high-profile coverage, especially with the advent of self-driving cars and Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo program that beat a professional Go player in March, 2016.

Not wanting to miss out on the trend, I began reading blog posts, tutorials, and doc pages on the mathematical foundations of different types of neural networks, and of course, how the hell to implement one. I definitely suggest Andrew Ng’s Coursera course, “Machine Learning” for an in-depth treatment of multi-layer perception neural networks. Most of the bleeding-edge neural network programming frameworks available to your typical data scientist are, not surprisingly, in Python. Here are a few of the deep learning tools I’ve read about:

These offerings range from full-scale Python libraries that allow you to write every aspect of a deep net from scratch (e.g. Theano) to smaller libraries (e.g. nolearn)that offer wrappers to deep learning backends like Theano and TensorFlow. R hosts many neural network packages too, but since so much of deep learning is focused on GPU computing (using graphical processing units to handle model training), most of the DIY deep learning world is centered in Python.

Deep learning is a huge field, and I’ve just begun to scratch the surface. Fortunately, there are dozens, probably hundreds of tutorials out there that will give you the illusion of letting you feel like you know what you’re doing. Basically all of the Python offerings are open source, so you’ll naturally be invited to a host of different tutorials, which is ten thousand times A GREAT THING. The only downside is, you’ll be classifying the MNIST numbers over and over.

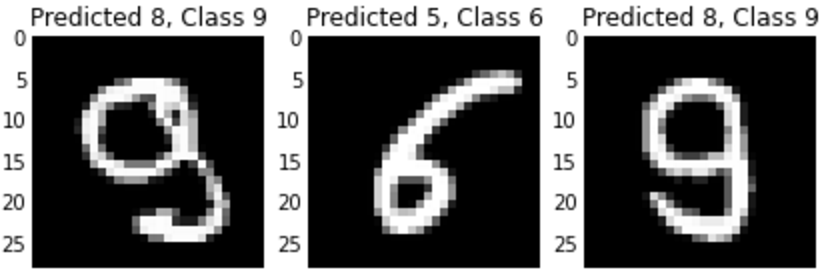

The MNIST numbers is a fully labeled set of 60,000 training and 10,000 test images, the images being handwritten digits, 0 through 9. Almost every intro to deep learning tutorial out there revolves around training a neural network on the training set and then minimizing the misclassification error of the test set. Very quickly you can have a model that only misclassifies about 33/10,000 digits, and the misclassified digits were poorly written in the first place:

While the MNIST set is big enough to merit GPU computing, I’m more interested in learning about neural network architectures first, not so much GPU computing. Thus, a set of 60,000 images pertaining to 10 separate classes is over-kill for me. I want to run a homemade example.

Why deep learning?

The MNIST numbers are a great resource, no doubt, but these tutorials centered on classifying the MNIST set can easily mask the complexity and patietence required to build a high-perforant deep network. Jumping in with an MNIST tutorial might make you forget why we’re even using neural networks in the beginning.

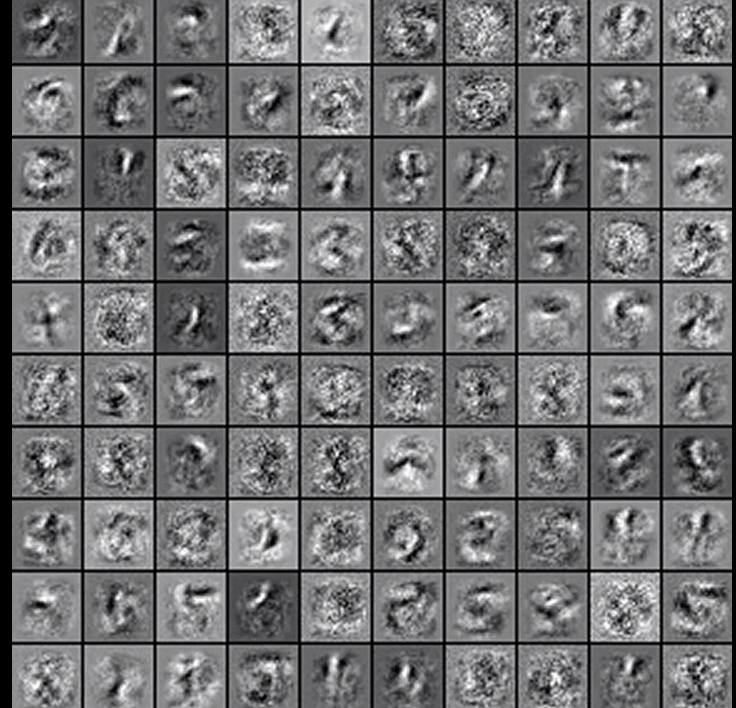

The underlying reason why we use a neural net with images (either multi-layer perceptron networks, convolutional neural nets, or maybe even autoencoders) is that they let us learn really good image bases in an unsupervised way. That’s the goal in most of machine learning, deriving bases (simple representations, the LEGOS, if you will) that comprise the objects in your training set. For example, here are some of the bases learned for the MNIST training set while training a multi-layer perceptron model:

That’s it. I mean, that’s the biggest reason - deep nets learn really good bases that aren’t confined to being linear combinations of the original pixel features (like PCA), or convex combinations of pixel features (like archetypal analysis), but seemingly arbitrarily complex, non-linear transformations of pixel features in the training set.

Outstanding questions that I have about deep learning:

Many things about deep learning go unaddressed in a typical walkthrough to a new deep learning framework like a Keras or a Theano. Here are a few questions I’ll hope to explore on my own that I feel are important to understanding deep learning as a tool and not a solution.

-

What are the dimensionality constraints for training a multi-layer perception model? Is it even possible to train a model using less than a few thousand training examples? Is there a ratio of n (training examples) to p (feature dimension) beyond which an MLP or a convolutional neural network would be particularly easy to train?

-

Is there a way to assess statistical significance using a neural net - e.g., can I get something like a standard error for the coefficients in a weights matrix between two layers of an MLP?

-

Besides bootstrapping or cross-validation, can I get some sort of confidence interval around the predictions coming out of, say, a deep net used for multi-class classification?

Meet the Greebles

Greebles look exactly how they sound, as in, they’re purple minions with weird phallic horns:

“Male” greebles have concave-up horns and “female” greebles have concave-down horns; they’re commonly used in psychological studies related to facial and object recognition, and according to Wikipedia they’re commonly found in psychology textbooks. In my greebles repo, you’ll find 160 color greeble images with 84 males and 76 females that I got from Carnegie Mellon’s TarrLab.

In the coming tutorials, I’m going to see how well I can train a host of models, including a couple of deep-nets, to classify greebles by “gender”. There is a “greeble generator” available through the TarrLab too, should we need a bigger set for training. But overall, I’m lucky to just have such a solid set of labeled, uniformly positioned, shaped, and colored images, all of which make the MNIST set such a good resource.

What I’ll explore with greebles

- Greeble decompositions: PCA “eigengreeble” decomposition, non-negative matrix factorization, archetypal/prototypical analyses

- Logistic and kernel-based classification methods

- Multi-layer perceptron neural nets

- Convolutional neural nets

- Autoencoders: similar to PCA, the autoencoder finds a low-rank approximation to an input

Greeble decomposition tutorial

To get started, check out the tutorial I’ve posted in my greebles repository for how to get started loading the greeble images, and how to start reducing the dimension of the initial feature space. Each greeble .tif file is 360 pixels by 320 pixels, so we have 160 greebles with each 115200 interesting features. No learning algorithm is going to be able to swim in such a high-dimensional situation, so I’ve used principal component analysis and non-negative matrix factorization as ways to reduce the dimension of our greeble set prior to fitting a classification model.