How bad is it? Exploring racial disparities in NCAA quarterbacking with an ETL pipeline

I am not an avid sports fan, let alone well-versed in the who’s-who of college football. But last fall, I was at the gym while ESPN was running through clips of the morning’s SEC (Southeastern Conference) games; they cycled through three games. It struck me as odd that all six teams on TV had white quarterbacks. The Fall of 2017 was the height of the kneeling NFL player phenomena, and statistics about the racial composition of the NFL were everywhere.

Perhaps the most widely reported statistic surrounding the NFL and race is that the league is comprised of about 70% African American players. Colin Kaepernick really kicked off the discussion of race as it pertains to football, and he’s a quarterback, which is inarguably the most important position on a football team. He was only one of the 5 starting black quarterbacks in the NFL (out of 32) in 2017. The question of racial dispairities quarterbacking is important - what does this say about what team management, football fans, and league commissioners tend to value in the person representing and commanding their respective teams?

Netflix's QB1 showcases a select few college-bound football prodigies.

Netflix's QB1 showcases a select few college-bound football prodigies.

So let’s explore it - how lopsided is white quarterbacking in D1 college football, and is it worse than the NFL? Is this a general problem affecting college football as a whole, or is it localized to certain conferences? Maybe it’s just “a few bad apples [teams]” that tend to only have white quarterbacks? All of the SQL, Python, and R code that I’m going to reference is available in my ncaa_quarterbacks GitHub repository, go check it out!

ETL best practices?

You - perhaps you’re a data scientist, maybe you’re a grad student - put a lot of effort into finding data sources and developing cool functions to munge websites or databases for their data, transforming it into a form that’s useful for you, and then asking something important from the fruit of your labor. Are users more interested in feature A or feature B? In which neighborhoods is the rate of people swapping out public transit for rideshare?

That is, you’re usually engaged in some sort of data ETL process - Extraction, Transformation, and Loading - for the purposes of being able to answer these questions. ETL always feeds some sort of downstream analysis or someone else’s data dependencies. There are lots of ways to refer to ETL processes, the nomenclature usually just changes depending on the scale of the ETL. People at companies who write the code to pull data from dozens of databases and generate reports on a recurring basis tend to call their work “data pipelining.” Companies often refer to this process, which could encompass several teams, as just “ETL”. The smaller-scale work that involves eviscerating websites for their free data is called “web scraping” or “web munging,” but that’s usually still captured under ETL.

Here are some best practices (not that I’m some sort of authority) that I’ve found to be useful guiding principles when managing a data pipelining project such as our college football project. Overall, scrapes (extractions) should be robust to small changes in the data source (for us, a website) and therefore modular, and other people should be able to reproduce your efforts!

- Use a database to store your data extractions instead of keeping the fruit of your scraping labor in individual files or directories.

- Separate your data ETL processes and code from any ensuing data analysis motivating the ETL in the first place.

- Make your database do the heavy work of data analysis instead of the ETL code. Use R or Python to filter/reshape/pivot/clean data.

- Reuse your code. Variance between websites is not so large that every site needs its an entirely fresh codebase, and code for loading data into a database should be completely independent of the tables/indices/documents you’re trying to modify within the database.

Building the database

The best reason for maintaining your extractions in a database is so that you can maintain the relationships between the different entities in your data. 2 months from now, are you going to remember how the data in players_positions.csv relates to teams_players.csv? Probably not, but a decent database management tool like JetBrains’ DataGrip will plot you a picture called an ER diagram, telling you how your different pieces of data fit together:

Our “college_football” MySQL database ER diagram

Our “college_football” MySQL database ER diagram

Each rectangle in the ER diagram is a table, and the arrows display primary key/foreign key relationships - how data in one table is linked to in another table. For example, each team has players, and each player has a position. We don’t need to store which player played which position on which team during which year all together in one table. We just need one table that holds references to other tables that represent (player, position, team, year) combinations. For example, maybe (player_id = 12, team_id = 4, position_id = 20, year = 2015) means “Kody Cook played quarterback for Kansas State in 2015.”

Launch the college_football MySQL database like this:

- Make sure you have

mysqlinstalled. Mac users can try installation withbrew install mysql. - Ensure your MySQL server daemon is running (Mac instructions)

- Run the

ncaa_quarterbacks/sql/deploy_db.shshell script.

cd ncaa_quarterbacks/sql

./deploy_db.sh <your username> <database password>

This will construct a database with 7 tables, one for each entity or relationship we’ll need: conferences, teams, players, positions, player statistics, conference-team relationships, and team-player-position relationships.

Extracting, transforming, and loading data with python

Scraping a decade’s worth of every college football player’s performance takes a bit of time and computing power - we do have 10 years’ worth of football games that span 12 conferences and include over 50,000 unique players and their performance statistics. Keeping this data in a few text files is a bad idea. But with a SQL database we can run the scrape once, load data into the database, and then query data from the database as needed. The database will enforce the relationships between players, teams, and statistics.

To run an ETL job, you should have three types of code - extraction code, transformation code, and loading code. In the (ncaa_quarterbacks)[https://github.com/ffineis/ncaa_quarterbacks] repository I’ve combined the transformation code with the loading code, but the transformation code is clearly outlined and flows straight into a load into the database.

Extraction + Transformation code

The ncaa_quarterbacks extraction code lives in code/scrapers. It’s easiest, if possible, to just transform your scraped data into your database’s conventions right off the bat. For example, store scraped conferences in a pandas.DataFrame with a conference_name column.

conference_scrape.pycontains a function to extract the names of different conferences and the years each conference was active.team_scrape.pycontains a function to extract team information: names and roster URLs. Teams are nested within conferences.player_scrape.pycontains a function to extract players from roster URLs (players are nested within teams) and another function to extract a player’s statistics once we know they’re on a roster.run_scrape.pyis a script that iterates over each year (cfbstats.com has data starting from 2008), pulling the conferences, teams, and player information for that year. Since there are many statistics to scrape for each of the thousands of players in an NCAA football program, teams are processed in parallel for any given year. Each table is represented, for now, just as a pandas.DataFrame. All of that data is put into a dictionary (keys are years) which gets dumped to a single serialized python file. Loading code unpacks this data and sends it up to our database.

Any web scraping Python code will likely center upon using the requests library to download the website’s contents and then using BeautifulSoup4 to extract the content’s meaning.

Loading code

There are really only two things main tasks you’ll ever be concerned with when it comes to ETL and SQL: (1) inserting new data that did not exist previously, and (2) updating old values with fresher ones. Doing either is pretty easy with the popular and foundational SQLAlchemy toolkit.

The way I use SQLAlchemy is not as a SQL expression language but more simply as a means to upload/download data and to execute raw SQL code. While this does not harnesses the full power of the SQLAlchemy toolkit, it lets me run actual SQL code, which is probably easier for most of my colleagues to understand if we haven’t all been exposed to the SQLAlchemy API.

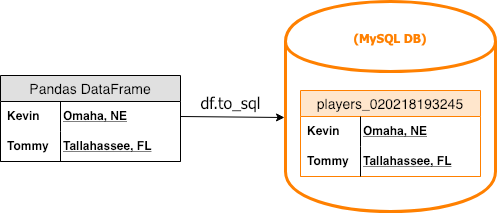

The basic workflow for loading data from python into our database is pretty simple:

- Move a pandas.DataFrame into the database by creating a temporary staging table with the

to_sqlDataFrame method.

- Write SQL commands to either insert new data into an existing table from the staging table or to update data within an existing table from the staging table. For example, perhaps we’re inserting new players into the

playerstable, or we’re updating some particular (existing) players’hometowndata.

- Drop the staging table.

All of the loader code is further wrapped within SQL transactions, so that if any part of the load fails, all changes made to the database during the transaction get automatically rolled back. Checkout the make_staging_table, insert, and update functions within code/sql/mysql_helpers.py for more details on the Python and SQL underlying the loading. Note the reusability of this code - for every table I want to insert new data into or to update, I really only need the insert or the update - this allows the loading code to be completely independent of the actual data being inserted or updated.

Labeling quarterbacks

The run_load.py takes the .pkl file resulting from the run_scrape.py scrape and loads the scraped DataFrames into the college_football database. After that, I downloaded 3 photos for each of the scraped 1652 quarterbacks from Google Images with the run_qb_photo_scrape.py script, and labeled them with a binary “is_caucasian” variable (1 = caucasian). I put the labels in a text file and used mysql_helpers.py.

Full disclosure - my labeling is based off of only a few images (and Google searches when the images were ambiguous), and my labeling could definitely be error prone! For many players it’s difficult to tell whether they’re caucasian, and in most of their photos they’re wearing full football uniforms. This is a sensitive issue, and I fully acknowledge my inability to fully recognize someone’s racial or ethnic background from such niave methods. Therefore my results are an estimate of the true level of whiteness among NCAA quarterbacks.

Results

About 71.1% of the quarterbacks appear to be white guys. If we assume that the non-African American quarterbacks from 2017 were all white guys (safe assumption - Latino and Asian quarterbacks have been few and far between), then 84.3% of the NFL quarterbacks were white. So the problem appears slightly less acute at the college level - and this pattern has held up over the last 10 years - but NCAA quarterbacking is still heavily disproportionately a white position.

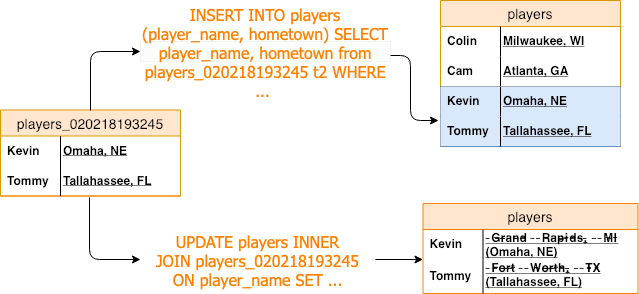

The Big Ten had the whitest quaterbacking, the Atlantic Athletic Conference the least white.

Trends in per-conference QB whiteness

Trends in per-conference QB whiteness

In terms of individual schools, here were the top ten most “whitely-quarterbacked” teams from 2008 to 2017. All of them played exclusively white quarterbacks:

| Team | Number of D1 QBs (2008-17) | White QBs |

|---|---|---|

| Colorado State | 13 | 13 |

| Old Diminion | 5 | 5 |

| UC Berkely | 12 | 12 |

| Northwestern | 13 | 13 |

| Central Michigan | 11 | 11 |

| Washington State | 10 | 10 |

| Western Michigan | 11 | 11 |

| UMAss Amherst | 6 | 6 |

| Stanford | 13 | 13 |

| BYU | 14 | 14 |

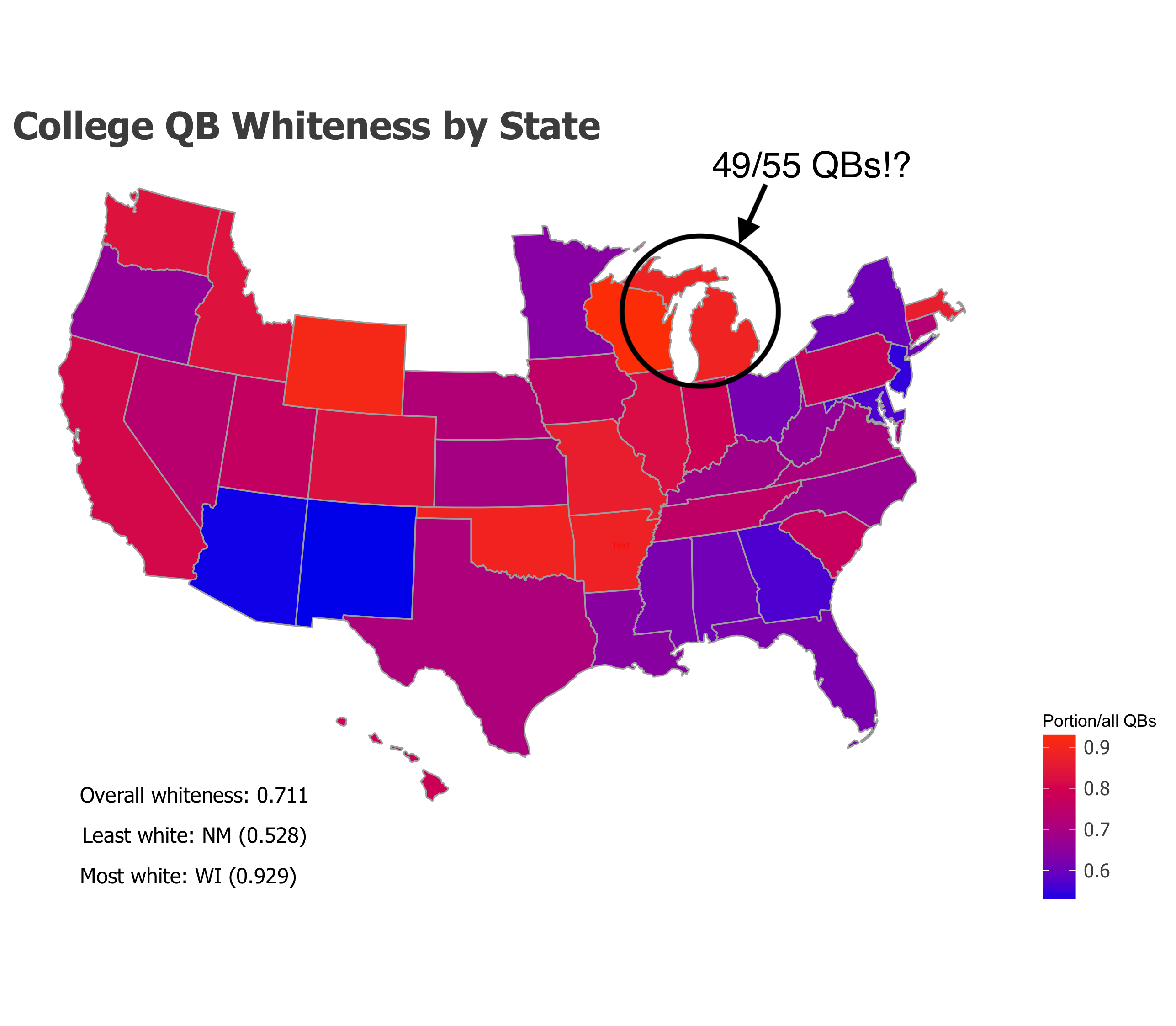

Given the Big Ten was the whitest conference, it’s probably not surprising to see that 3/10 of the states with the higest rates of white quartbacking were in the Midwest:

| Team | Number of D1 QBs (2008-17) | White QBs |

|---|---|---|

| Wisconsin | 14 | 13 |

| Wyoming | 11 | 10 |

| Oklahoma | 28 | 25 |

| Michigan | 55 | 49 |

| Arkansas | 25 | 22 |

| Missouri | 15 | 13 |

| Colorado | 42 | 35 |

| Idaho | 28 | 23 |

| Washington | 22 | 18 |

| Illinois | 38 | 31 |

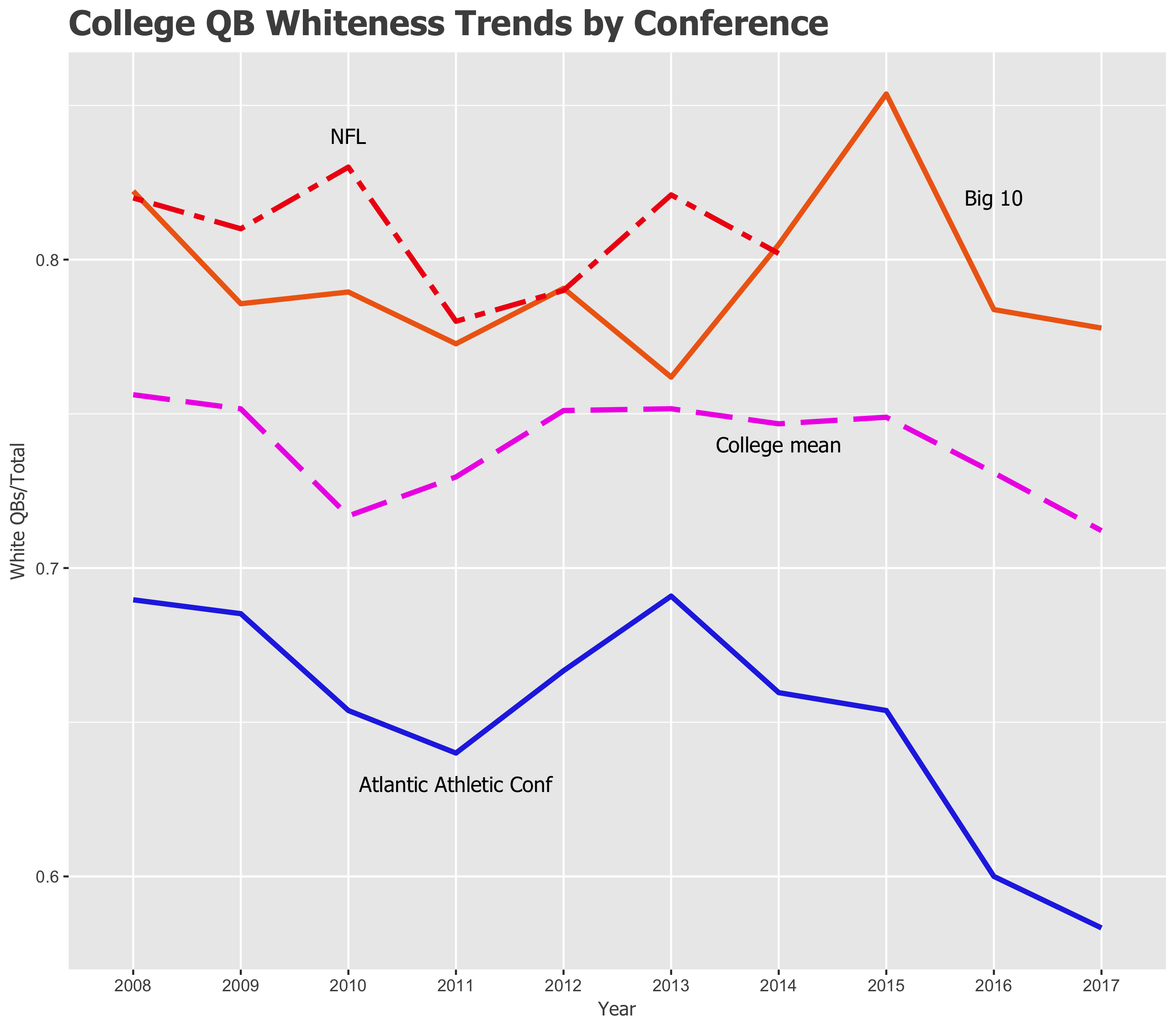

There’s no correlation between the number of quarterbacks a school had (which is a heuristic measure of the size of the program), and the level of whiteness of their quarterbacks. Really, the only D1 team with racially equitable quarterbacking is the University of Arizona with only 5 white quarterbacks out of their aggregate 15.

Distribution of QB whiteness across schools

Distribution of QB whiteness across schools

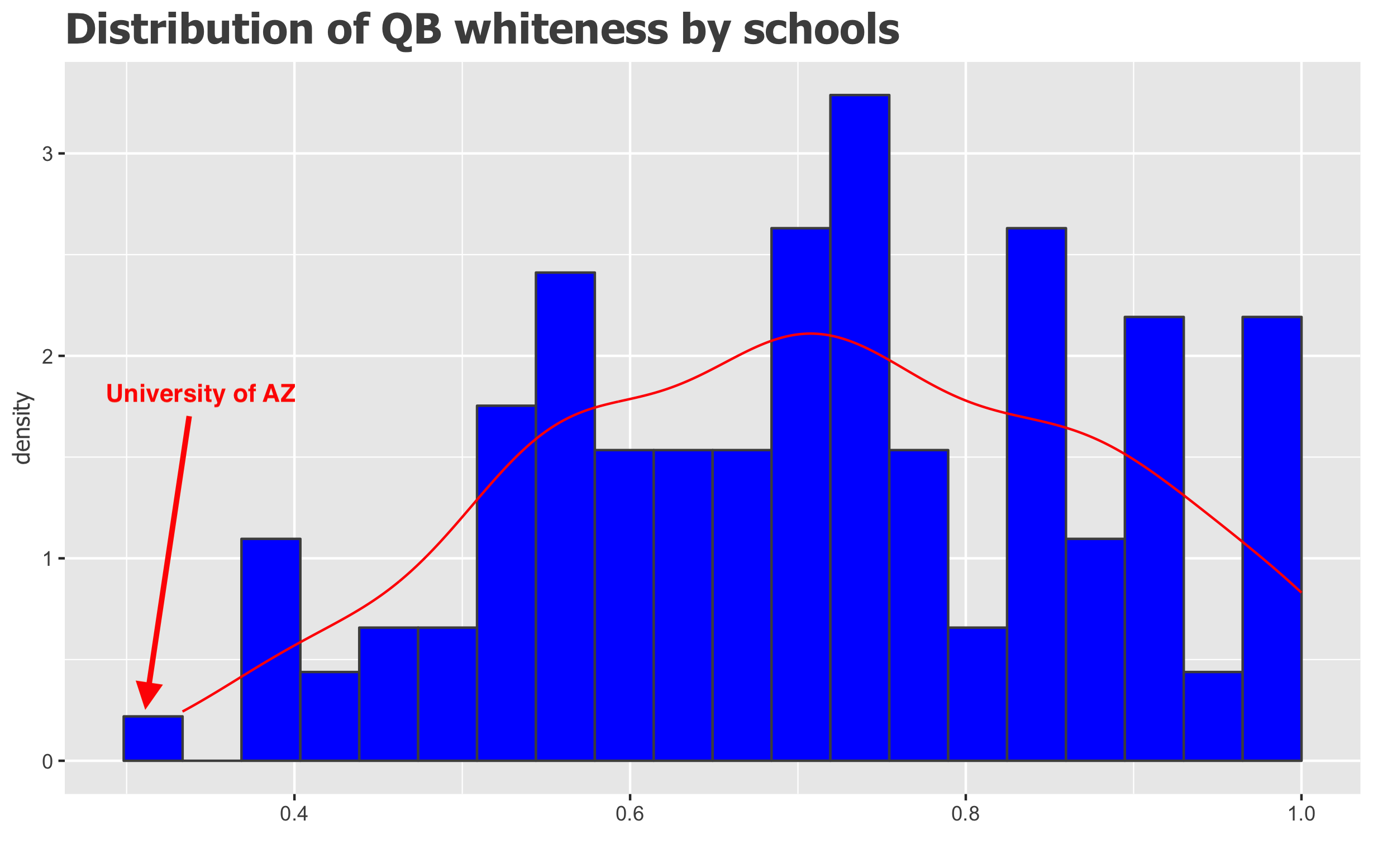

In terms of sheer numbers, nobody messes with Texas. They had 168 D1 QBs, 121 of whom were labeled caucasian (72%, so, about average). Ohio was a distant second with 92 quarterbacks, 58 of whom were caucasian (63%).

Per-state QB whiteness

Per-state QB whiteness

The fact that Michigan had 49 white quarterbacks out of a state aggregated 55 is strange given the number of (pretty high profile) D1 programs: U Mich, Michigan State, Western Michigan, Eastern and Central Michigan. Each one of these programs staffed at least 80% white quarterbacks, despite being some of the most high-profile, heavily recruiting football programs in the nation.

Unsolicited opinions beyond code, ETL

This analysis is really just an executive summary, and someone could make the argument that the rate of white quarterbacking needs to be put in context with the rest of the team - would it really be that unfair for a team that’s 80% white guys to have a white quarterback? Would it be unfair for a team without much of a recruiting budget, located in a predominately white area (e.g. Idaho) to have exclusively white quarterbacks? I’d love to have program revenue or budget data to study the impact of football program funding (which would serve as a proxy for recruitment ability) on average QB whiteness.

But at the end of the day, the vast majority or QBs are (very disproportionately) white, and I think that most reasonable people would agree that this isn’t a good thing. Does this problem start at the college level? Definitely not. This is completely anecdotal, but for anyone interested, I highly recommend watching Netflix’s original series “QB1”. To me, it highlights how much it takes beyond just pure athleticism to become a star college quarterback. Tate Martell’s entire family (one of three featured QBs in season 1) moved to Las Vegas just so he could play at in an elite high school football program. White quarterbacking at the college level is probably just as much a reflection of the racial wealth gap and other forms of systemic and historic racism as it is anything else. A symptom of a larger problem.

But at the very least, I’d like to posit that it’s on the wealthy, enormous football programs (if not the NCAA itself) to fund youth quarterback mentoring programs with diverse young quarterbacks. If we’re not going to pay elite football players, the least we can do is demand that publicly-funded programs dedicate resources that will make their teams 10, 20, and 30 years out more equitable.